Posted on June 28, 2023

Introduction

It goes without saying that textile manufacturing is a competitive field. For example, despite enormous and growing demand for disposable textiles, there remains stiff competition for market share. Textiles can also be high value products, especially following the advent of advanced functional textiles (such as those used in healthcare applications for sensing; or ultra-strong textiles for use in aircraft parts). Moreover, a need for sustainability and circularity is driving innovation across the textiles industry; with this wave of innovation comes a swath of intellectual property (IP) on which to capitalise.

To be sure of protecting and utilising IP more cost-effectively and to block competitors, businesses do well to triage IP associated with manufacturing processes.

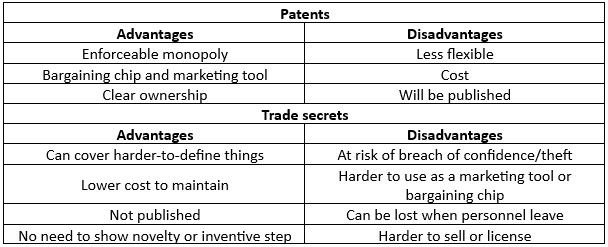

Check with your patent attorney whether features are better protected with patents or held back from the public domain as trade secrets. To kick-start your thoughts, this article provides a short summary of patents and trade secrets with an example in this sector.

Headline features of patents and trade secrets

Patents are essentially a bargain in which the owner of an invention shares with the world how to put their invention into practice in return for a time-limited monopoly on that invention.

In contrast, trade secrets can be used to hold back know-how, which tends to be rather specific yet might not be easy to define or protect through a patent.

Example invention

It’s always helpful to consider a concrete example! Here is a process for making a blended textile containing cork particles. The resulting textile is for use in vehicle interiors, ski suits, insulated keep-cups and similar applications.

The process includes:

- mixing staple cotton fibres with a filler and cork particles (the filler is polylactic acid and/or a polyurethane);

- raising the temperature of the mixture from step (1);

- adding a curing agent to the mixture;

- extruding the mixture (including the curing agent from step (3) into continuous fibres;

- curing the mixture; and

- coating the obtained fibres with a few micrometres of synthetic rubber.

The blended textile product has been on the market for several years and has been a big commercial success. However, the process for making the product remains a secret and the mill is keen to protect their innovation via a patent application for the process and/or as trade secrets.

The inventors know that the best cotton fibres to use come from a plantation in Uruguay that specialises in a certain cotton cultivar.

In summertime at their North Carolina plant, it’s normally humid and hot, so they introduce a cooling step between (5) curing the mixture and (6) applying the PET coating. They also wipe down their apparatus more frequently in these conditions.

If more than about 50 % of the cotton staple fibres are more than about 1 cm in length, TEM imaging shows they will wrap particularly well around the cork particles. However, when these lengths of fibres are used, the mixing step will not result in a homogeneous enough mixture unless it is blended for at least 2 hours in their reactor.

The combination of cork and a synthetic rubber coating gives just the right level of waterproofing while providing a soft product with good energy return (a feeling of “bounce” or “spring” when handling the product). Using both a cross-linked (cured) material and a coating finish imparts strength, so placemats can be used repeatedly before they are discarded.

Although the synthetic rubber coating is not biodegradable, the inventors are looking into biodegradable alternatives.

Triage of subject matter for protection via a patent or holding back as a trade secret

The overall process is a good fit for patent protection. The process can be precisely defined in the “claims” of a patent application. (The claims are the part of the application setting out the scope of the monopoly that stops other people using the invention.)

Depending on the scope of the claims, the patentee can stop unauthorised parties working in a broad area around their core commercial process/product. This may force competitors to use less effective processes.

For example, an independent claim of the patent application could require “wood particles” (with a fall back to “cork particles” in dependent claims, case “wood” is not found to be novel and inventive). This would keep competitors out of a broad area around cork.

That said, the inventors clearly have valuable learned knowledge around process optimisation which is too specific to appear in a claim and is also difficult to define. Not all of it is needed to work the patentable invention. Much of it is not really an “invention” of the type required to satisfy a Patent Office of patentability (especially “inventive step”). Yet it gives the mill a real advantage over competitors. There is no need to disclose it in a patent application and risk competitors taking it up.

The choice of cotton supplier is one element of such know-how. The cooling step has similar considerations. Depending on the business landscape, the cooling step and increased cleaning/wipe-down frequency is, or are, probably something to hold back as a trade secret.

The preferred cotton fibre length might be worth including in the patent specification because it seems to result in a special advantage that could help confer inventive step (the wrapping around cork particles, evidenced by TEM). However, this might also be something quite specific that the inventors want to hold back to stop competitors knowing about it. Whether this feature goes into the application or is held back will depend on the commercial landscape and should be thoroughly discussed.

The cork and synthetic rubber combination is something that needs to go into the patent application, because it is part of the key inventive concept, of getting good waterproofing while maintaining energy return. However, the patent application would ideally extrapolate to other woods and other polymers and not be limited to this precise combination.

The biodegradable alternatives to PET are something to keep track of as they may, in and of themselves, be a new invention worth protecting via a patent application. This is because they seem to be a broad concept that can be clearly defined.

Commercialisation

The mill is looking to sell their products to retailers. They are also looking to partner with apparel brands to develop new ways to use the textiles, potentially in new forms of synthetic leathers for shoes – in particular, they are considering licensing their process to one of these brands.

Patents will be a marketing tool and a bargaining chip in these negotiations. Especially for the mill considering licensing the process, valuing the licence can depend in large part upon clear indications as to the extent of the intellectual property.

In contrast, it is difficult for prospective investors to value trade secrets without knowing the content of those trade secrets. Disclosing them to investors before a deal risks leaving the business vulnerable if the deal falls through. After a transaction has been agreed, the mill might be more forthcoming with knowhow. One thing the mill can do is to hint at the existence of trade secrets (and say they are robustly documented internally) as a signal to investors and potential partners.

Flexibility

Ultimately, the mill wants the best of both worlds when it comes to how they protect their process.

A patent is limited to what was written in the original application that was filed for the patent. It will also be limited to the specific countries in which the mill chose to protect the process. Although there is normally plenty of time (months or years) during which to pin down those countries, once they have been chosen, they are often impossible to change. Finally, the patent can last for a maximum of 20 years from the date of filing the patent application. It will also be published by Patent Offices.

Those features of patents are not necessarily disadvantages. For example, 20 years is a long term of protection compared to the pace of industry.

Published patents can also put competitors on notice and act as a signal of a mill’s robust IP presence.

Used wisely, trade secrets might offer flexibility to complement patents. Theoretically, a trade secret has no expiry date. They can cover all sorts of different things. They may also cost less to maintain, not requiring the payment of official fees, particularly “maintenance” fees paid at regular intervals to Patent Offices to keep a patent in force.

However, trade secrets can be vulnerable to theft, reverse engineering, or accidental disclosure, potentially resulting in loss of competitive advantage. Although there are legal provisions that exist to protect trade secrets, once the “cat is out of the bag”, the harms that have been done may not be outweighed by the compensation available through the courts (and the mill may not even be made aware of the theft of its trade secrets). If personnel leave, even if they had agreed to leave trade secrets behind them it is hard to be certain, particularly if they move to a competitor.

Final remarks

More could be said on this topic than this short article allows. If you are interested in leveraging trade secrets and patents together, especially in textiles manufacturing, please reach out to your usual contact at Abel & Imray; else, get in touch with the author at anne-marie.conn@abelimray.com.

Meanwhile, for a flavour of patents and trade secrets in other sectors, please visit: